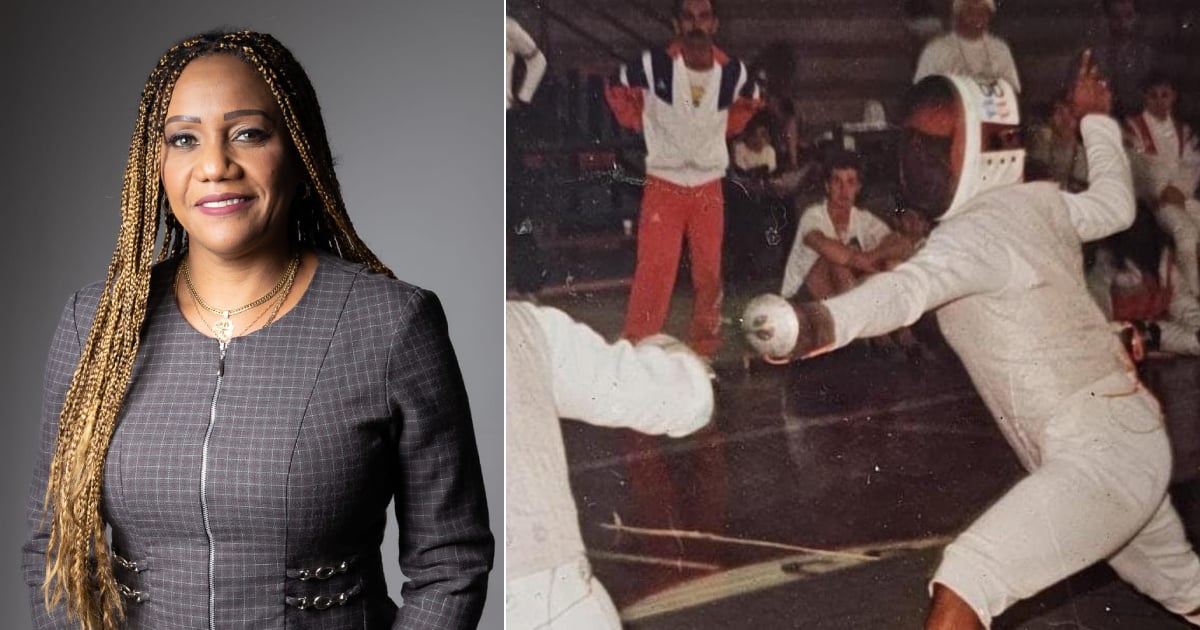

Migsey Dusu Armiñán, a distinguished fencer from the days when fencing thrived in Cuba, is a double Pan American champion from Winnipeg '99 and an Olympic participant in Sydney 2000. Her captivating nature and kindness have won her the friendship of many, making her a successful figure in the United States today.

What do you do for a living, what did you study, and what is your daily life like?

I specialize in rehabilitating individuals with various bodily pains, as well as those recovering from accidents or post-surgery. Upon arriving in this country, I pursued further education. I hold multiple licenses, including Physical Therapy Assistant, Massage Therapy, Medical Assistant, Full Specialist, Real Estate, Life Insurance (0214), Electrocardiography, Security Licenses D, G, W, Personal Trainer, and Notary Public.

Have you found time for anything besides studying? Haha. Yes, indeed. Knowledge is invaluable, and here you need the "papers" for everything. Although I maintain all these licenses, my primary focus is rehabilitation. I own a physical therapy center called M&M Rehabilitation Center at 10250 SW 56 St, in Miami.

My days are exceedingly busy, between being a therapist, an administrator, a mother, and a wife. Managing a business, especially multiple ventures, is no easy feat. Besides, I run a security company, Reinforced Security Services, providing guard services to various facilities.

I also own a cleaning business, Shine Bright 305, offering services exclusively to shopping centers. Additionally, I am involved in real estate and life insurance sales. Don't ask me how I manage all these; I simply do!

Never before in my professional life have I encountered a former athlete as accomplished and tenacious as Migsey Dusu. She's truly remarkable.

When did you arrive in the United States, and how?

I came in 2005, entering through Mexico and crossing the border from Reynosa into the U.S.

Tell us about your family. Will your daughter pursue sports?

I am married to Mariano Leyva, a former coach of the Cuban boxing team and the Mexican Olympic boxing team. He decided not to return to Cuba during the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Currently, he is a Therapeutic Massage professor at Praxis Institute and the head of the Therapeutic Massage program.

We have an 11-year-old daughter, Katherine Mariana Leyva Dusu, who, despite her athletic lineage, is inclined towards the arts. She started modeling at two, paused during the COVID pandemic, and now sings, plays piano, and clarinet.

My mother and brother, along with my two nephews, are here with me. In Cuba, my father, three sisters, and three nephews remain.

Looking back, where did it all begin?

I was born in Santiago de Cuba on January 25, 1972. Initially, I was into athletics, but I didn't enjoy it and wasn't very good. I tried high jump like Javier Sotomayor but feared the bar, so I switched to hurdles. The first day, I fell, and my coach said, "Get up and keep going." That was the end of my athletics journey. I then turned to fencing, inspired by my friend, Mirialis Oñate.

Who were your coaches?

I fondly remember all my coaches from my fencing days. At the EIDE "Capitán Orestes Acosta," Jorge Garbey and Fernando Bárzaga; at ESPA Nacional, Pedro José Hernández Duquezne and Lourdes Osorio Pang (La China); and at the national team (Cerro Pelado), Osvaldo Puig, Nelson Guevara, and Efigenio Favier. Each played a role in shaping the fencer I became.

I'd like to acknowledge Osvaldo Puig, who significantly helped me on the national team.

What did being left-handed mean for your fencing career?

In my era, being left-handed was an advantage in fencing, as there were fewer left-handed competitors, making it challenging for right-handed fencers. Nowadays, the playing field is more balanced with equal numbers of left and right-handed fencers.

What defined you as a fencer?

I was known for my defensive style, strong hands, and being more tactical than technical. Fencing has evolved significantly since my time, but it remains dear to my heart despite my busy life.

Why has Cuban fencing declined?

Cuban fencing once held Olympic and global prominence. Unfortunately, post my era, the sport has deteriorated. The current generation lacks weapons, competitions—essentially everything. The foundation has collapsed entirely. Even during my time, the female foil and saber lacked competitions, but we benefitted from the male foil's frequent matches, which inadvertently helped us improve.

Our top Olympic and world contenders participated in nearly every World Cup, while we, the female foilists, were limited to two events: the Villa de La Habana, and possibly another. Supposedly, there wasn't enough budget.

The other part of our training was "fencing with heart." I spent 14 years on the national team, often preparing for a competition only to be told a week prior that there wasn't enough budget. The idea of a female foil team tour in Europe was merely a myth. The current situation is likely worse, with no national tours due to the country's dire state. They blame the embargo, but the truth lies within their own actions. It's infuriating, and deep down, they know it's not true. Speaking up against this is risky, as I personally experienced. I lived in the "monster" and know its workings because Cuba devours its own.

Which fencer do you admire globally and nationally?

Globally, I admired the Italian fencer Giovanna Trillini. She was a universal fencing icon, participating in five Olympics and winning eight medals. Nationally, I admired Bárbara Hernández for her style and strength as a competitor, along with Caridad Estrada.

Migsey Dusu graced the podiums of World Cups, Pan American, and Central American Games, as well as the World Universiade in Palma de Mallorca 1999. That year was exceptional for her career, as she became the individual foil champion and led the winning team at the Pan American Games in Winnipeg.

How did your departure from the national team unfold after 14 years?

An elite athlete requires proper nutrition, training resources, and preparation. The rest is mere talk, which Cubans excel at. They hold meetings at the Ciudad Deportiva, and when an athlete speaks the truth, they face severe backlash. I often refrained from speaking to avoid being expelled from the national team.

Once, I had a controversial interview with journalist Rafael Pérez Valdés from Granma newspaper. Afterward, interviews were banned unless approved by the national commissioner. It was tyranny at its peak, as everything had to be filtered to fit their narrative.

This wore on me, and I left the national team in 2003, not on my terms. Here’s what happened: I had a boyfriend who left Cuba for good. I made it clear that if he left, we’d part ways because I didn't want to leave the country. At that time, I was preparing for the 2003 Pan American Games in the Dominican Republic.

Despite being Cuba's top fencer and Pan American champion, the State Security found out about my boyfriend's departure. They ordered that I couldn't leave the country under any circumstances. I had a knee injury, which they tried to use as an excuse to prevent my participation.

Professor Rodrigo Álvarez Cambras at the "Frank País" Orthopedic Hospital treated me, but Dr. Antonio Castro gave me clearance to train. However, at Cerro Pelado, they insisted on constant checks and fabricated a knee tear to halt my training.

The Party officials claimed they couldn't "trade athletes for medals." It was absurd, considering how many times I competed injured for their demanded results. They barred me from the Villa de La Habana, knowing my performance would secure my spot in the Pan American Games in the Dominican Republic 2003.

I didn't get to retire as I wished. I wanted to defend my continental title, but they denied me that chance. It was then I decided to leave Cuba—a decision I hadn't previously considered. I was tired of the hypocrisy. It was painful, but it allowed me to see through the communist regime and realize the opportunity to start anew in the United States.

Now, 20 years later, I live in this great nation that has offered me citizenship and countless opportunities. I’ve built a life with my daughter, husband, home, cars, and businesses. Here, I walk free and fulfilled, knowing that with determination and faith, anything is possible in liberty.

I thank God, and ironically, even them, for pushing me to see the truth and make the life-changing decision to leave that oppressive system behind.

Insights into Migsey Dusu's Journey and Cuban Fencing

How did Migsey Dusu Armiñán's career transition after moving to the United States?

Once in the United States, Migsey pursued education and obtained various licenses in physical therapy and other fields. She now owns a rehabilitation center and multiple businesses, thriving in her professional and personal life away from Cuba.

What challenges did Cuban fencing face according to Migsey Dusu?

Migsey highlighted the lack of resources, competitions, and support for athletes in Cuba, which led to the decline of fencing in the country. The oppressive system and poor infrastructure contributed significantly to this downfall.

Who inspired Migsey Dusu to take up fencing?

Migsey was inspired by her friend Mirialis Oñate, a fencer at the EIDE, which led her to pursue fencing after an unsuccessful stint in athletics.