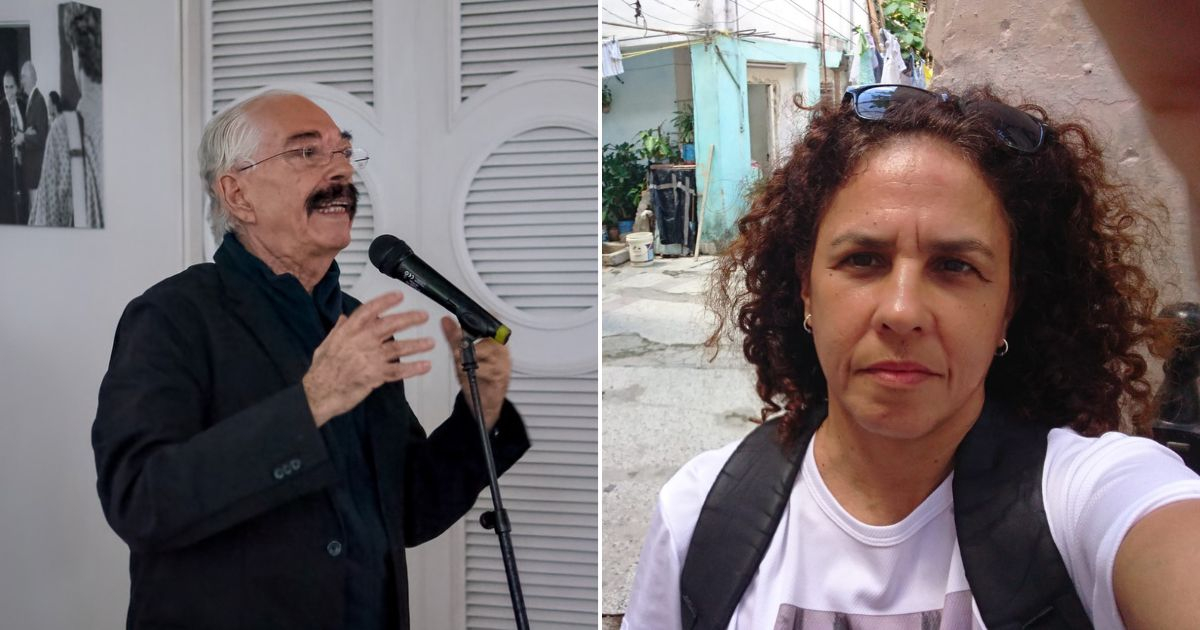

The Cuban journalist Yania Suárez has publicly condemned her expulsion from the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba after attending a screening and discussion of the documentary "Landrián" by filmmaker Ernesto Daranas. In a detailed post on her Facebook profile, Suárez noted that she went to the event with several questions regarding Nicolás Guillén Landrián's life, particularly concerning his alleged connections with the Cuban Committee for Human Rights (CCPDH), founded by Ricardo Bofill in the 1980s.

"I had questions, but I let others speak first," she remarked, highlighting that during the discussion, Helmo Hernández, the director of the Ludwig Foundation, described the institution as a "cult space for Guillén Landrián," a "pioneer in promoting his work," and a "bulwark of 30 years against censorship." However, when Suárez raised issues about significant biographical omissions and mentioned the filmmaker's potential involvement with the CCPDH and his role in the First Exhibition of Dissident Art, she was abruptly interrupted.

Suárez recounted how Hernández, visibly upset, accused her of being paid to push an agenda within his space, interrupting her narrative about Landrián's participation. "Nearly hysterical, he refused to allow what I was doing. The sound engineer shut off the microphones. Helmo revoked my right to speak," she alleged.

In response to being silenced, Suárez called Hernández a "hypocrite," pointing out his resemblance to the censors, despite Landrián himself having been a victim of censorship in Cuba. Ultimately, she was forced to leave the venue. Before departing, she challenged the director's actions and accused him of "ad hominem censorship," attacking her personally instead of engaging with her arguments.

Suárez wrote her account to expose the mediocrity and falseness of certain performances that, since the Revolution, feign democracy. She concluded by asserting that such events aim to "sell foreign visitors the illusion of accepted dissent within the Revolution," when, in fact, censorship remains rampant. Suárez mentioned possessing an audio recording of the incident but expressed reluctance to release it, as she dislikes causing scandals.

The Silenced Legacy of Nicolás Guillén Landrián

In an investigation published by Hypermedia Magazine, Yania Suárez argues that the official recovery of Nicolás Guillén Landrián's legacy is marred by strategic omissions regarding his biography, especially his potential ties to the Cuban Committee for Human Rights. Suárez suggests that this "rescue" effort is spearheaded by the ICAIC, the very institution that once persecuted and censored Landrián, which has led to a selective reinterpretation of his history.

One of the most overlooked aspects, according to Suárez, is Landrián's possible involvement with the CCPDH, a group that exposed human rights abuses in Cuba and faced severe repression by the regime. She points to reports from America’s Watch and testimonies from exiles indicating that Landrián might have collaborated with this committee during his final years on the island.

Suárez highlights that in 1988, Landrián allegedly participated in the First Exhibition of Dissident Art organized by CCPDH members in an apartment across from Jalisco Park. This event showcased works by marginalized artists and featured microphones to denounce victims of Cuban repression. Witnesses affirm Landrián's presence and his associations with key dissident figures like Adolfo Rivero Caro, suggesting a deeper commitment to opposition than the official narrative admits.

Within Cuba, the reconstruction of his biography has deliberately avoided these elements, choosing instead to frame him as a misunderstood artist and victim of certain officials' extremism, without acknowledging his direct challenges to power.

Suárez believes this omission is part of a well-defined strategy to soften his story to fit the official Revolutionary narrative, where only the mistakes of a few individuals, not the system itself, are blamed for past abuses. She questions the authenticity of this "rescue," asserting that Landrián's legacy will only be fully vindicated when his dissent is acknowledged, and the repression he endured for defying the regime is recognized.

Censorship has been a constant throughout the Cuban regime's history, systematically used to silence any voice challenging the official narrative. Cuban filmmaker Pavel Giroud recently reported on social media that the 40th edition of the International Jazz Plaza Festival canceled the screening of his documentary "Manteca, Mondongo y Bacalao con Pan" (2009), which was scheduled for February 1st. "Apparently, they regretted programming my documentary at the 23 y 12 cinema (Jazz Festival program)," Giroud posted on Facebook.

In January, the state-run Cubavisión channel announced on its official Facebook page the withdrawal of the telenovela "Violetas de Agua," which aired daily at 2:00 p.m. The statement cited "technical reasons," but the announcement has sparked speculation among viewers as another possible instance of censorship.

However, controversy arose on social media when it was revealed that the telenovela featured the controversial influencer and regime opponent Alexander Otaola. This issue is not new. The Assembly of Cuban Filmmakers (ACC) ended 2024 with a strong call to defend creative freedom and denounce the censorship affecting the audiovisual world. In a statement shared on Facebook, the organization emphasized the challenges faced by independent filmmakers and demanded a change in the country's cultural policies.

Understanding Censorship and Dissent in Cuba

What led to Yania Suárez's expulsion from the Ludwig Foundation?

Yania Suárez was expelled from the Ludwig Foundation after she questioned omissions in the documentary about Nicolás Guillén Landrián's life and his potential ties to the Cuban Committee for Human Rights, leading to a confrontation with the foundation's director.

Why is Nicolás Guillén Landrián's official story considered incomplete?

His official story is seen as incomplete due to strategic omissions regarding his potential involvement with dissident activities and organizations, such as the Cuban Committee for Human Rights, which challenge the official Revolutionary narrative.

How does the Cuban regime use censorship?

The Cuban regime uses censorship to systematically silence voices and works that challenge or contradict the official state narrative, as seen in instances like the cancellation of documentaries and television shows.